Jean Oostens

Songs of the Phony War1

Most historians place the beginning of World War II (WWII) at the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. For the other nations soon to be involved, France and Great Britain (who would become the Allied), a pause of several months followed their Declaration of War on September 3, 1939. The two opposite sides relied on their respective lines of fortification, the Ligne Maginot on the French side, the Ligne Siegfried, on the German side. In the early months the war was mostly spent as a sitting war, where loudspeakers rather than canons were aimed at the opposite side. Garrison in the forts had the leisure to dry their laundry in open air, and the French public caught that spirit in a song which quickly became popular:

Nous irons pendre notre linge sur la ligne Siegfried Pour sècher le linge voici le moment.

Nous irons pendre notre linge sur la ligne Siegfried

Le beau linge à maman, les vieux mouchoirs et les ch’mises à papa.

En famille on lavera tout ça.

Nous irons pendre notre linge sur la ligne Siegfried Si on la trouve encore là.

Nous irons pendre notre linge sur la ligne Siegfried.

We will hang our laundry on the Siegfried Line

This is the moment to dry the laundry.

We will hang our laundry on the Siegfried Line

mom’s pretty linnen, the old handkerchiefs and daddy’s shirt.

All in the family we will wash all that.

We will hang our laundry on the Siegfried Line If it is still around.

We will hang our laundry on the Siegfried Line.2

In Ostende (a Belgian resort on the North Sea) on New Year’s Eve 1939, in the presence of the Belgian minister Marcel-Henry Jaspar, the local band played this song, even though Belgium was at that time strictly neutral. Never mind, everyone cheered and asked for several encores.3 Soon, the arrival in France of the British Expeditionary Corps was an occasion to revive old favorites of World War I: The Rose of Picardy and It’s a Long Way to Tipperary (translated this time as: Traversant la Manche une seconde fois.. – Crossing the Channel a second time).

Other French songs downplayed the determination and the military preparedness of Germany. They were aired by loudspeakers over the lines, more to reassure the French soldiers than to frighten or demoralize the enemy. This of course brought a false sense of security to the people and contributed to the Allied collapse when the German army bypassed the Maginot line by invading the Low Countries in May-June 1940.

Sadness of Soldiers Away from Home

As war went on, soldiers on both sides felt the sorrow of being away from home. We go now to the Libya-Egypt theater, where Italians, and later Germans fought the British. Far from their home, the German soldiers listened for comfort to a German-speaking radio station located in the Balkans. There, as the cool night fell on the desert, the draftees of the Afrika Corp listened over and over to Lili Marlein, a song written in Hamburg in 1915 by Hans Leip at the age of 22 while on his way to the front line. Robert Schultse’s new melody composed just before WWII in 1938, for this older World War I text, quickly became the most popular song in Germany:

Vor der Kaserne vor dem großen Tor

Stand eine Laterne, und stebt sie noch davor,

So woll’n wir uns da wieder she’n

Bei der Laterne wolln wir stehn,

Wie einst Lili Marleen, wie einst Lili Marleen.

After their victory at El Alamein, soldiers of General Montgomery’s British Eighth Army, in particular Tommie Connor, rendered the song in English as follows:

Underneath the lantern by the barrack gate,

Darling I remember the way you used to wait.

Twas there that you whispered tenderly

that you loved me. You’d always be

My Lili of the lamplight – My own Lili Marlene.

Time would come for the roll call

time for us to part. Darling I’d caress you

and press you on my heart.

And there ‘neath that far-off lantern light

I’d hold you tight, we’d kiss good night

My Lili of the lamplight – My own Lili Marlene.4

As the German fortunes of war faded, a curious French version quietly circulated in occupied France and Belgium. In this writer’s memory, it started as:

Près de la caserne quand le jour s’enfuit,

La vieille lanterne s’allume et luit.

Un soldat Allemand vint à passer.

Je lui ai demandé: « Pourquoi pleures-tu? »

et il m’a répondu:

« Eh, oui, nous sommes foutus.

Eh, oui, nous sommes foutus. »

By the barracks as the day was flying by The old lantern would light up and glow. A German soldier came by,

I asked him, “Why do you cry?” and he answered me:

‘Oh, yes, we are all doomed. Oh, yes, we are all doomed.’

While Jazz and Blues were banned in Germany as decadent during the war, the musical tradition of the Jazz Français flourished in Paris, with “Le Hot Club de France,” and artists like Ray Ventura and many others. Occupying German soldiers often made up their most avid audience.

Serious Music is a Serious Matter in Germany

Jazz was not the only type of musical taboo in Germany. “Jewish Music” was not to corrupt the Aryan culture. This prohibition started years before the war, when Jews had to resign from public offices and when musicians with remote Jewish ancestry saw their performances canceled and their works banned.

This situation applied to living as well as past composers, including Felix Mendelssohn-Bartoldy – even though his family had converted to Christianity. Many artists with international fame or good connections left the country, including Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter, and Arnold Schoenberg. Even the pure German celebrity, Richard Strauss, could not keep his position as director of the Reichsmusikkammer when it was found that his librettist, Stefan Zweig, was a Jew!5 Strauss himself, rather than protesting by canceling his conducting engagements – as Toscanini did at the Bayreuth Festival – did not hesitate to stand in for those conductors who either renounced or had their bâtons taken away by the Nazis.

Strauss, however, continued his career as a composer without further interference. He was the author of the Olympische Hymn for the 1936 games in Berlin. Germany made those games a propaganda platform for the Nazi regime. Then in 1940, he composed his Japanische Festmusik, to celebrate the 2600th anniversary of the Japanese Empire as a tribute to an ally of Germany. The première took place in Tokyo on October 27 of the same year. Another Axis partner, Italy contributed a Symphony in A Major by Ildebrando Pizzetti. Though not a member of the Axis, France felt obliged to send a congratulatory composition and the French government commissioned Jacques Ibert, who at the time was director of the French Academy at the Villa Medicis in Rome. Ibert created a fifteen-minute Ouverture de Fête, for the occasion.6

Briefly considered as a “Class 1 War Criminal” after the war, Strauss explained his position by saying that he had felt compelled to serve the cause of German music. He had also used his connection with Baldur von Sirach, Austria’s Gauleiter, to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law and his two grandsons in exchange for his silent acquiescence.

Strauss seems to have had no regrets about the Nazi regime’s responsibility in the ravages of the war. On the contrary, he blamed the allied bombings for the destruction of all the opera houses that had premiered his works over the years.7 Also, the complete recordings of his work he had just directed for a German record company were destroyed by firebombing in 1945. These events, in his mind, were all disasters inflicted on Germany by the barbaric furry of the Allies.8

The Kultuur Bund – Later known as KuBu

A strange exception to the Jewish exclusion from the Nazi’s artistic world was allowed under the aegis of Joseph Goebels’s own ministry of Kultuur und Propaganda. Starting at the end of 1933, “Jüdisch Kultuurbunden” were started in Berlin, Cologne, Frankfurt and Stuttgart, as a way of mitigating the interdiction forbidding Jews to attend movies and concerts in existing places. Special theaters and concert halls were set aside with government supervision for Jewish musicians and playwrights to perform exclusively for a Jewish public. Jewish composers, musicians and actors were paid from the proceeds of the sale of subscriptions. Tickets could only be purchased by Jews and were advertised exclusively in Jewish newspapers. Each performance was attended by two Nazi representatives who monitored the content of the work performed.

This alternative arrangement had originated with two Jewish artists, Kurt Singer and Kurt Baumann. Since Jews could no longer spend their money on cultural events now reserved for Aryans exclusively, such resources could be redirected to support the artists who were out of their jobs because of the very same racial laws. A parallel market of the performing art would thus come into being.

Hans Hinkel, an ambitious Nazi party member since 1921, endorsed the idea as a way to carve a niche for himself in the propaganda bureaucracy. The Nazis liked the deal: it created tax revenue for the state, it removed the embarrassment created by the large number of unemployed artists, and it kept the two Cultures in “separate but equal” facilities, shielding the Aryan population from Jewish influence. To the rest of the world, the KuBus (as they were called) offered a response to those who would complain about the bad treatment of the German Jews.

After a few seasons, many of the provincial KuBus were unable to cover their expenses and had to be closed. The one in Berlin survived under the umbrella of the Reichsverband, created in 1935, until the infamous Kristalnacht on November 9, 1938.9 At that time, all performances were suspended sine die. The artists and stagehands thought it was the end of their livelihood and that they would be “transported” east (i.e. to Buchenwald, Dachau or another concentration camp).

But the Nazis had not forgotten that the Berlin Kultuurbund still had a good propaganda value. Its general secretary, Werner Levie, was ordered to reopen the performances as soon as possible, as a token of a return to normalcy after the “unpleasantness” of Kristalnacht. However, 200 artists and other prominent Jews had been placed in “protective custody” in concentration camps. They were held without charge in what is known as “Nacht und Nebelen” (Night and Fog). Levie was able to negotiate the release of his artists as a condition for restarting the performances.

The reopening on November 22, featured the play Rain and Winter by Somerset Maugham. It attracted a full house, a statement by the Jewish community that they would not yield to the intimidation of the Nazi mob.

The reopening of the Kultuurbund came with important reorganization of the scope of the association: it expanded its responsibilities to Jewish books, movies and newspapers all over the Reich. This came with strict supervision by the Nazis of the finances to make certain that the hefty tax on the gross receipts was duly paid. All hiring and expenses needed to be approved by the Ministry of Propaganda.

A copy of one of the last programs announces the presentation Die Musikantische Stunde (The Musical Moment).

One should notice that all performers have either Israël or Sara as middle name. This was the result of an edict forcing all Jews to adopt such middle names to mark them as outcasts. Later an even more constraining obligation was imposed, all Jews were required to wear the yellow Star of David, sown on the outside layer of their clothing.

On September 11, 1941, when preparations for the “endlösung” (Final Solution) were in their final phase, the Ministry put a brutal end to eight years of activity of the Kultuur Bund. Those participants who had not been lucky enough to emigrate were dispersed through the various forced labor camps.

Teresin Fortress, Emperor Jozef II’s Gift to Czechoslovakia

The Nazis mounted a similar organization on a smaller scale in Theresienstadt, a town near Prague in the former Czechoslovakia. This garrison town, Teresin Fortress, was erected at the end of the 18th Century by Austrian Emperor Jozef II to prevent German invasion of this part of his Empire. With Jewish “volunteer” labor from Czechoslovakia, a model concentration camp was constructed in 1941. In analogy to the Kultuurbund, it served as an example to the world that Jews were treated quite well in Germany.

For all practical purposes, the place was a transit camp where most Jews would stay for only a short while until deportation to death camps, only to be replaced by new arrivals collected in various parts of occupied Europe. Its atmosphere is well described in the fictional saga by Herman Wouke, War and Remembrance.10

Many talented artists incarcerated there produced cultural activities against all odds. As an example, Kurt Singer, one of the initiators of the Kultuur Bund, taught a well-attended seminar on music history.11

In 1938, after a short trip to the United States to raise funds for the KuBu, Singer realized the hopeless future of that enterprise. When his ship reached Amsterdam, he sent a heartbroken resignation letter to his associates and found shelter in Holland. He was safe there until 1940, when the German invasion of Belgium and Holland brought him again under Nazi rule. His status allowed him the “favor” to be sent to Theresienstadt in 1943. He did not see the end of the war, and died there.

Some of the best Czech musicians and artists were sent to Theresienstadt. Unable to restrain the human spirit of creativity, they created remarkable new works and animated the artistic life of the community in their difficult circumstances. Some works composed during their captivity were preserved. Several recordings are also available on compact disk, including:

Stimmen aus Theresienstadt – Performed by Bente Kahan, vocalist and guitarist, with supporting musicians.12 Includes: Ein Koffer Spricht (A Suitcase Speaks), Die Kartoffelschärin (The Potato-Peeling Woman13), Theresienstädt, Die Schõnste Stadt der Welt (The Prettiest Town in the World), and Polentransport (Transport of Poles).

Chamber Music from Theresienstadt, 1941-1945 – Performed by the Hawthorne String Quartet and Virginia Eskin.14 Includes quartets, a trio, and a sonata by Gideon Klein and Viktor Ullmann.

Viktor Ullmann and Gideon Klein were two of the most representative Jewish composers of art music to be imprisoned at Theresienstadt. Ullmann (b. Prague 1898, d. Auschwitz 1944) had been a student of Schönberg, and wrote quarter-tone music. He was arrested in Prague in 1942, taken to Theresienstadt, from where he was “transported” on October 16, 1944 to Auschwitz. He died there two days after his arrival.15

Gideon Klein (b. Prerov, Moravia 1919, d. Fürstengrube, Silesia 1945) completed his musical studies at the Prague Conservatory in 1939, at the moment when the annexation of Czechoslovakia to the Deutsche Reich made him subject to the Nuremberg racial laws which banned Jews from all public positions. As the best piano graduate of the Conservatory, he was to have represented his school by playing the Dvořák Concerto at the celebration of the 100th birthday of the composer. He was also denied permission to accept a scholarship to study at the London Royal Academy of Music.

In December 1941, Klein was taken into Terezin, the camp having just been enlarged to accommodate several tens of thousands of Jews in Theresienstadt. By 1942, he found himself in charge of teaching children separated from their parents. There, with conductors Rafael Schächter and Karel Ancerl, composers Hans Krasa, Pavel Haas, and Viktor Ullmann, singers Karel Fröhlich, Lonja Weinbaum, Romuald Süssmann, Heini Taussig and Fredy Mark, he encouraged the development of a true musical atmosphere, and soon became one of the principal figure of the cultural life at the camp. This activity originally started entirely underground, and was later more or less tolerated by the Germans. In this framework, Klein organized many chamber music concerts, including Quartets by Brahms (Op. 60) and Dvořák (Op. 84) for piano and strings which were performed twelve times. He also wrote a large number of compositions which survived. Before his transfer to Auschwitz, Klein entrusted them to his friend Irma Semecka. Irma stayed till the end at Terezin and gave the manuscript to Gideon’s sister, also a musician, who had survived the war. On October 16, 1944, nine day after finishing his last composition, a string trio, Klein was transferred to Auschwitz, then to Fürstengrube, where he was killed around January 27, 1945.

Books written by the rare survivors of Theresienstadt document the plight of those well-to-do German Jews who were lured there by the prospect of spending the war in relative comfort either in recognition of their special station in pre-Nazi German social life or by large cash bribes to Nazi officials. Once there, ” …they suffered from disease, starvation, exhaustion, overcrowding and the persistent threat of deportation. Between 1941 and 1945, about 33,000 people died in Theresienstadt of disease or malnutrition, while about 88,000 were transported to the death camps in the east.”16

Radio and Propaganda

During World War I, radio waves, using Morse code, were a highly specialized means of communication used by the armed forces. During the Twenties and Thirties, AM radio had become a household item. Advertisement was the main source of funding for the many private radio stations. As war came, the propaganda services of both sides used the new medium both to increase the fighting spirit of their own people, and to undermine the morale of their adversaries.

The message had to be sugar-coated with some entertainment: popular music for the troops, classical music for the intelligentsia. Musicians, as with all citizens, were touched by the dynamics of war.

The Glenn Miller story is a good illustration of the means invested in both aspects of the war of the airwaves. Before the war started in earnest for the United States with the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, American draftees were not the most enthusiastic soldiers. Glenn Miller was told to play the regular army marching tunes. He decided to “jazz it up,” and miraculously the steps of the marching platoon took a martial turn for the best. His idea made its way to the top brass of the army, and soon Glenn Miller found himself conducting the United States Army Air Force Band.

Miller’s music sold by the millions, and in mid-1944, with the Allied landing and campaign in Normandy, Major Glenn Miller and his “American Band of the Supreme Allied Expeditionary Force” extended their services to entertain British Armed Forces as well as their own. His repertoire included many hits: Don’t Sit under the Apple Tree (with anyone but me), In the Mood (a Boogie Woogie), Chattanooga Choochoo (about a train that will “choochoo you home” from New York’s Pennsylvania Station to Chattanooga) and even, to mark the good relations with the fighting Russian Army, The Volga Boatsong, spiced with American syncopation!

In October 1944, Glenn Miller and his band of 50 musicians contracted with the American Broadcasting Station in Europe (ABSIE) for a series of performances meant to lure the Germans into listening to a German-language propaganda broadcast. The British used it to undermine the fighting spirit of the German troops stationed on the continent. Those recordings involved some 50 musicians (all Armed-Force personnel) and an occasional female vocalist. Some of the pieces (Long Ago and Far Away for one) were sung in German, and Glenn Miller was even coached to announce the songs himself in phonetic German. Starting on Wednesday, November 8, 1944, six weekly half-hour broadcasts were aired under the title Musik für das Wehrmacht, at a time when the Third Reich was being crunched between the Anglo-American armies on the West and by the Soviets on the East.

The recordings were made on vinyl discs and stored in the archives of the ABSIE. Even though there were some negotiations to commercialize them after Glenn Miller’s untimely death in December 1944, the ABSIE and the Hollywood owner of the copyright could not agree on suitable financial arrangements, and the recordings waited for half a century before being discovered and remastered into a pair of compact discs.17

News bulletins of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) being beamed towards the occupied territories of Europe were introduced by V for Victory in Morse code, using the first four bars of Beethoven’s famous Fifth Symphony. Churchill would use the famous V for victory gesture as a model throughout the war.

A lesser known symmetric situation came into being shortly after the June 6, 1944 landings in Normandy. Radio Bruxelles, a Belgian broadcasting Institute controlled by the Germans, launched “Le Bureau des Bobards et des Canards” with the same acronym, BBC (meaning, “The Bureau of Gossips and Hearsay”). This was a pastiche of the genuine news bulletins so many patriotic Belgians managed to hear despite the constant German jamming of the radio waves. The producers of this radio show capitalized on the irritation and grief caused by the “collateral damage” of the Allied bombings. The bombing method, they said, was called “Assimil” (after a well-known method for learning foreign languages): “A six mille mètres d’altitude” (phonetically: at an altitude of six thousand meters – where bombing accuracy was problematic, to say the least).

Another sample of their wit and humor was the question: “On which front would the Anglo-American foot soldiers rather be sent: Italy or Normandy?” The answer (to be interpreted phonetically): “Italy, because they would rather die at Milan (1,000 years) than at Quarantan” (40 years), a little town in Normandy where fierce fighting was taking place.

In a comic manner, the tune used to introduce the American movie industry’s Oliver Laurel and Stanley Hardy comedy series, introduced Radio Bruxelles’s program in the same manner Beethoven’s four-note motive from the opening of the Fifth Symphony introduced the British Broadcasting Cooperation’s news announcements.18

After the war was over, a large backlog of American movies reappeared on European silver screens. One day, this author, after enjoying a steady diet of Laurel and Hardy reruns, came home casually whistling that catchy tune. Remembering the wartime radio show, his mother scolded him for singing such unpatriotic music. She had not seen the movies and her son had a hard time convincing her that this was a perfectly legitimate piece of film music and not a neo-Nazi recognition signal!

Music for War Movies

There is a great treasure trove of magnificent music for war movies but the most popular ones were produced after the war with more impressive budgets and better means than during the hostilities. Although the music and movie industry did not command top priority for scarce resources during the war, their value for sustaining the morale and for political propaganda was not lost. Movie stars showed their patriotism in action-filled war movies, singers toured the world entertaining the troops. Composers pitched in too: Axis sympathies in Latin America would have helped the German submarines operating in the Atlantic, and the rich mineral resources of the continent had to be preempted by the Allied. Aaron Copland’s goodwill mission to South American in 1941 was one such example.

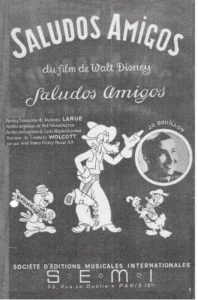

An additional goodwill gesture came in the form of Walt Disney’s movie Saludos Amigos. It covered a visit to Brazil and other South American countries by none other than Donald Duck and Goofy. They were joined in Rio de Janeiro by a happy-go- lucky parrot named Jose Carioca. All three went along to the tune of their signature song The Three Caballeros. Additional music was contributed by Ethel Smith playing Maria de Bahia on her organ and by the Aquatic Ballet of her Bathing Beauties.

Conclusion

Conclusion

As we have seen in these examples, music (and art in general) affects the lives of people under the stress of war. And we have seen music’s action to be a double-edged sword. For those suffering from the circumstances, music became a powerful support to keep their hopes alive. For the masters of the situation, it meant a means to achieve their agenda.

The Terezin example illustrates in a tragic fashion the coexistence of those two aspects: the Nazis used the musical talents of their inmates to lure Jews into a golden cage and to keep them there, unsuspecting of their future fate, death for most of them. At the same time, the very same music was making a statement on the indomitable spirit of the people playing it. The gloom, hardship, and agonies encountered were counterbalanced by creativity and performance. Their statement affected not only the inmates, but thanks to the surviving scores, all future generations.

Endnotes

The author is grateful to Robert Doty, Yolande Oostens, Sida Roberts and Wesley Roberts for their careful review and constructive suggestions in the writing of this article. The article originated as a term paper for the course History of Music II at Campbellsville University

1 Even though during the period so named, Sept. 3, 1939 to May 9, 1940, the activities on the western front were subdued, fighting took place on the seas. On May 10, the German armies bypassed the Maginot Line by invading Belgium, Luxemburg, and Holland.

2 Unless otherwise stated, all translations are by the author.

3 Pierrre Stephany, 1940 – 366 Jours d’Histoire de Belgique et d’ailleurs (Bruxelles, Belgium: Ed. Paul Legrain, 1990), 112.

4 Reader’s Digest Book of Popular Songs, (New York: E. B. Marks), 202.

5 George Marek, Richard Strauss: The Life of a Non-Hero (New York City: Simon and Schuster, 1967).

6 In an interview with Wesley Roberts, April 2, 2002.

7 Richard Brubank, Twentieth Century Music (New York City: Facts on File, 1984). This text lists many of the monuments of musical importance which were destroyed during the war.

8 Ibid., p. 216.

9 To protest the expulsion of Polish Jews to the Polish border (which the Polish government did not allow them to cross) a Polish Jew had shot the first secretary of the German Embassy in Paris, and this became the pretext for organized riots in the major German cities: synagogues were burned and Jewish stores were smashed by mobs. The broken glass littering the street as a result of the action gave the name of Crystal Night to what at that time was the most violent act of anti-Semitism of the Nazi regime.

10 Herman Wouk, War and Remembrance (Boston: Little, Brown, 1978).

11 Gerty Spies, My Years in Theresienstadt, trans. Jutta R. Tragnitz (Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, 1997), 81.

12 Stimmen aus Theresienstadt, featuring Bente Kahan and supporting musicians (compact disc recording; Plaene Verlag, 2001).

13 It refers to Hedda Grab-Kernmayr, a well-known alto, who was first assigned to the potato detain. She soon was allowed into the musical program where she really belonged.

14 Chamber Music from Theresienstadt, 1941-1945, featuring the Hawthorne String Quartet and Virginia Eskin, piano (compact disc recording; Channel Classics NI, 1993).

15 Ingo Schultz, “Ullmann, Viktor” The New Grove Dictionary of Music, Second Ed., S. Sadie and J. Tyrrell, eds. (London: Macmillan, 2001).

16 Spies, op. cit., jacket flap.

17 Glen Miller: The Lost Recordings – The American Band of the AEF, featuring Dinah Shore, Irene Manning, Johnny Desmond and Ray McKinley, 2 compact discs (Middlesex, England: Happy Days, a division of Conifer Records). Editor?s Note: Liner notes for this recording are now available online at: http://www.tarcl.com/palmer/miller/notesc.html#ted (accessed March 3, 2012).

18 Readers may hear this tune online at: www.laurel-e- hardy.it/html/download/audio/music-mp3.htm, by clicking on “Laughtoons” (accessed March 9, 2012).